29 November – Hoping against hope

Advent 1

29/11/2015

Jeremiah 33:14-16

Psalm 25

Luke 21:25-36

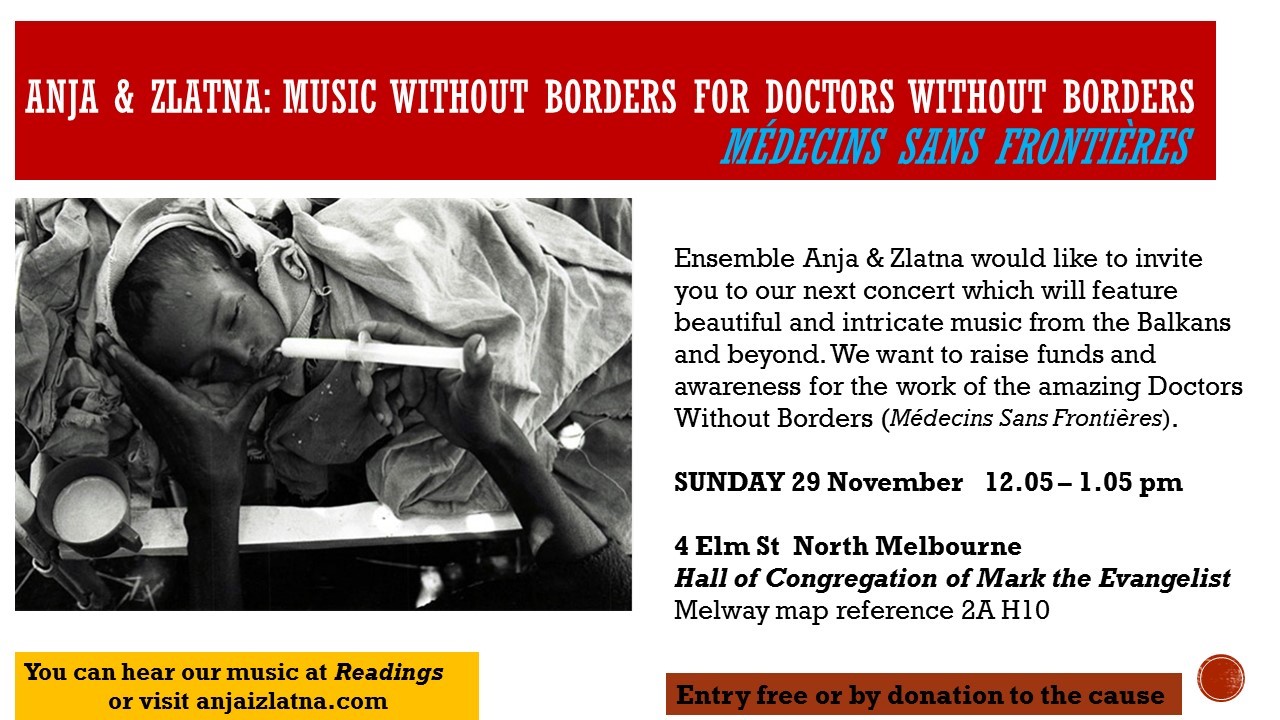

I hope we have a good turnout for the concert this afternoon.

I hope the fuel lasts until I find a petrol station.

I hope she doesn’t say I’m going to need root canal treatment.

We hope for all sorts of things.

The hopes I’ve just listed are rather weak ones. Their weakness is in that they are about things over which we have no real control. They are more wishes which the powers might perhaps grant us, if we are lucky, or they are the outcomes we would effect if we were God. These are hopes in the face of what is already determined. An outcome is already written; we just don’t know yet what it is. “I hope that the sermon is not too long, and that there’s no more nonsense about Time Lords or zombies.” Alas it is too late, and hoping will make no difference: it is already written!

The nature of hope in the Christian confession is not weak in this sense because Christian hope is not about what we would do if we were God, but about what God will do. The question then becomes, what would God “do”? This is not quite straightforward, and the answer depends on whether we imagine ourselves to live in the realm of myth, or of history.

We begin with myth. Perhaps some of you have watched Mythbusters on TV. It is one of the silliest shows on the box, although I so want to be able to do the stuff they do to test what they test: blowing things up, smashing them into each other, abusing crash-test dummies and blowing more things up! For our purposes this morning, however, the important thing is not their methods or any particular myth they might bust but the very meaning of “myth” itself in “mythbusters”. Within the show, a myth is a story about what might happen under certain circumstances: will a broken drive shaft flip a moving car? Can you ski behind a passenger liner? What they test is whether the rumoured thing is true or not; if true, it ceases to be a “myth”. This is how myth tends to operate for most of us: a myth is something which is not true.

More profoundly, however, myth is not about what is true but why certain things are true. The process of mythologising is one in which what we can see or experience is interpreted as a sign of the divine order of things. We might imagine that because a king has all the power, money and pretty women, this is because the gods have ordered things to be just so. (At least, a lot of kings have presumed this to be the case.)

Myths declare that what is clearly the case is not only the case but is necessarily so. This is how the world is because this is how it is made to be. More than this, how the world is then has consequences for what can happen next. The myths by which we live determine or guarantee our position or our fate. On this understanding, it is both obvious and necessary that all Palestinians are terrorists, that men are superior to women, that the market will find the correct level, that I have to have the latest model of my favourite iThing, that what I have was given as a blessing for me and not for you, that we won the war because God was “mit uns”. (You don’t have to agree that all these things are obvious or necessary, only that many often have agreed just that!)

Myths of this kind interpret how the world is to be part of a deeper ordering. Historically, this ordering has been religiously conceived: what is happening happens because of the activities of the gods. If we see that each year the grain grows, and then dies, and then does the same next year, we might imagine that this reflects the dying and rising of a god; in the case of the Romans, this was accounted for with the goddess Ceres (as in “cereal”). But religion and its gods are not an essential part of the dynamic. The important thing is that the mythologised world is, quite literally, hopelessly static. There is nothing to hope for but the next step in what is already predetermined. We do not drive but are driven.

Now, I said that what we might hope God might do is a matter of whether we think we live in a mythological world or an historical one. For this to make sense we not only have to re-think what “myth” means but also to re-imagine what “historical” means.

For most of us, most of the time, history is the stuff-that-happened. This is how history is taught in schools and features in public discourse. In this simple sense, history is everywhere, because things are happening all the time. The first Australian peoples have a history, the second peoples have histories which intersect; the Russians and the Chinese and the Africans all have their histories.

We tell ourselves that we are interested in our histories because they tell us something about who we are; just think of the enormous interest in family history these days. But when history tells us who we are, it begins to take on the characteristics of myth. If I am merely evolved from scum on the surface of a primeval pond, then what does that say about my freedoms here and now? If I am a person who was treated badly – even abused – in my early years, how does that affect my future? If my people have been terribly persecuted in living memory, what rights and claims does that give me here and now over others? In scenarios like these what happens next is often thought to be implied by what has already happened. And so there is not much to “hope” for here; rather, we read our futures off our past. This is not very different from the idea that there are gods behind every rock and tree who make happen what will happen next.

Distinct from this sense of history is the notion of history which appears for the first time with ancient Israel. Here history occurs for the first time. Of course, this makes no sense in the normal understanding of history: there was plenty happening before Israel appeared on the scene. What I mean is that in Israel, for the first time, human beings were offered a different sense of the relationship between where they had come from and where they were going. This brings us, finally, to our focus text today from Jeremiah as a concrete instance of this different feel for history.

Jeremiah preached before, during and after the fall of Jerusalem in 587BC. For the most part, his preaching described in no uncertain terms the disaster coming upon Jerusalem. Our reading today, however, comes from a small section in the wider collection of Jeremiah’s preaching, known as the Book of Consolation. This is comprised of a series of oracles which speak of a time beyond what was at immediately hand, when a restoration would come.

In this prophecy, two things are declared which contradict the static, hopeless mythologising of world events. First, it is declared that the meaning of the terrifying events unfolding around Jerusalem at that time was ambiguous. When what happens next is predetermined by what has already happened, then it is clear what will happen and why, for only certain things and conclusions can follow. If Jerusalem falls and the Temple is sacked, this becomes proof that the Judeans were wrong about the power of their God, and so can now only hope in vain. But Jeremiah has already preached the fall. His preaching has not been a discovery of a power operating in history of which his people were ignorant, but has been a revelation of the nature of history itself – a revelation of the nature of our lives together and with God. We are not caught up in the inexorable unfolding of some pattern of history, or the interplay of divine powers hidden under the surface of our experiences. We are in fact, potentially, entirely free at any particular moment.

This freedom is not always a freedom to change what might happen next. Having taken the political choices it had to that point, Judea may well still have been overrun, or at least humbled, even if it repented before God but this need not have been experienced as punishment or rejection. A God who takes up the part of “the widow and the orphan” (James 1.27; cf. Isaiah 1.17) will still be God to a people humbled in political defeat, if that defeat is not confounded by its own political pride.

The second thing which Jeremiah’s preaching opens up is hope which is neither a vain wish nor simply knowledge of the next thing which must happen as history unfolds. The name new name for Jerusalem after the restoration will be, “The Lord is our righteousness”. This “righteousness” is not a religious or moral quality but has more the sense of security, surety, defence, vindication, guarantor, or fortress. Jeremiah says of this promised community that it will be vindicated or guaranteed by “the Lord.” But his invocation of “the Lord” here is a polemic, a contrast. It is not merely that it will be “the Lord” who does this but that it will not be something else, some other candidate which guarantees or defends. This is in stark contrast to the situation during the time of Jeremiah’s ministry, in which the guarantors of Judah were thought to be its possession of Solomon’s Temple, its status as the elect of God, its army, its walls, and the intrigues of its political strategy on the international stage. The people had mythologised their existence – made it a necessary thing: We are this, therefore we can expect that; we are God’s people, therefore God will protect us; We have fallen, therefore our God is no real God. Yet What Jeremiah proposes is not a necessary but a chosen thing and, so, potentially quite unexpected: God is not powerless, but punishes; and God will yet honour you who, by most measures, are not worthy of honour.

We make history not when we do some extraordinary thing which will deserve its own chapter in the history books; we make history when the next thing which happens is a free choice, which creates possibilities no-one could have anticipated.

We make history when we turn aside from what has to be done to take up something which doesn’t have to be done but which is more important. We make history when, having all the facts, we find ourselves not compelled but free to decide what to do about them.

Hope for the future is not to be found in strategies which have mapped out where things are likely to go or theories which specify our next step. Such strategies and theories are like a law written on tablets of stone: permanent because carved into stone. Rather, hope for the future is found in the God who chooses us, regardless of what we choose, of how we calculate. This is a law written on hearts – perhaps even law as heart – God’s heart, and ours.

There is only hope where there is freedom. We, for the most part, are not free. We are taught what to expect, and we expect it. We calculate and measure and judge, and generally act accordingly. And we are subject to the same calculations, measurings and judgements.

There is only hope where there is freedom. The God of Jeremiah, and our God, is free in this way. Free to embrace what is unworthy, to lift up again what he has cast down, to fill what become empty and heal what has been broken. This is hope which looks for more than can be seen, hopes against “hope” for a future it has no right to expect, but is learning to expect it anyway.

May the people of God hear that promise and be re-formed by such hope, that they may become more particularly the people of this God, and God be more richly praised. Amen.