27 February – On not knowing what we say

Transfiguration

27/2/2022

2 Corinthians 3:12-4:2

Psalm 91

Luke 9:28-36

In a sentence:

We don’t know what we see in Jesus, but we know that it is good

Many approaches have been taken to the story of the Transfiguration. Some imagine that we have here a dream sequence or a vision – something which only happens inside the disciples’ heads and but not “really” occurring in time and space. The story is so rich in symbolism that the symbols themselves cry out for recognition, to the extent that questions of “what really happened” become quite secondary. Others have thought that this is a resurrection narrative that has been dislodged – deliberately or accidentally – from the end of the gospels to become something of a hinge point in the middle of the narrative. Others, of course, have taken it to be a reliable account of a historically “objective” event.

Our approach today won’t be to untangle these tightly knotted and confused approaches but simply to take the story at face value, and dive in at one particular point. In response to the strange change in Jesus, Peter apparently gathers his senses and speaks on behalf of the disciples: “Master, it is good for us to be here; let us make three dwellings, one for you, one for Moses, and one for Elijah”. Our focus text today will be the remark which follows: Peter has spoken, “not knowing what he said”.

We’ve long heard that this comment characterises Peter’s state of mind at this point. Like the callow teenager who has long loved from a distance a pretty girl in his class, only to respond with something utterly stupid when one day she speaks to him, so Peter is generally cast as blurting out the first thing which comes into his head, “not knowing what he said”. On this reading, he might as well have said, “…the slithy toves / Did gyre and gimble in the wabe”.

But biblical texts are economical. We already know that Peter and co. are out of their minds with fear. His building proposition, and naming this as incoherent, scarcely seems necessary.

We might, then, come at this another way. The Greek word behind “dwelling” is translated in other places as “tabernacle”. The Tabernacle was a tent-like structure in which God dwelt before the construction of the Temple. This is, then, a heavily loaded word – not merely a “place to stay” but having connotations of a holy presence. In the prologue to his Gospel, the evangelist John writes, “…The Word became flesh and made his dwelling among us” (John 1.14). John uses the same word here: the Word “tabernacled” among us.

In this light, Peter’s proposal of tabernacles becomes less silly than naïve. That is, tabernacles might be entirely appropriate but does Peter understand what that would mean? Has he grasped what it means that Jesus is in the same room as Moses and Elijah?

The Transfiguration story follows an episode in which Jesus puts a question to his disciples, Who do you say I am? To this, Peter responds, You are the Christ. Jesus then goes on to explain what will happen to him. In Mark and Matthew’s version of the story, this greatly offends Peter, who demands that such things must not be allowed to happen. Jesus then hammers Peter in return, naming him “Satan” and announcing that Peter, in effect, has not understood what he himself has said – what “Christ” means.

Luke doesn’t have that part of the story. Still, perhaps Peter’s announcement about the tabernacles is the same: “not knowing what he said” is about saying the right thing while not understanding what it means, or saying the wrong thing but, at a deeper ironical level we don’t yet recognise, being precisely right.

This naïve irony is not an unusual experience – certainly not merely a “religious” experience:

“Will you take this man, to have and to hold in the covenant of marriage, loving, comforting, protecting and faithful

as long as you both shall live?” “I will”, she said, not knowing what she was saying.

“Let’s start a family,” he said, not knowing what he was saying.

“We would like to offer you the job”, they said, not knowing what they were saying.

“You are the Christ”, Peter confessed, not knowing what he was saying.

“Let us build a tabernacle”, Peter said, not knowing what he was saying…

Or consider our own current deliberations:

“Let’s amalgamate with another congregation”, said the one, not knowing what he was saying.

“Let’s find another place to call our own”, said another, not knowing what she was saying.

As a community, we have before us a range of options, about which it can be easy to speak and yet not know what we are saying. If we are ignorant of the facts or simply ignoring them, we have a responsibility to expose those deficiencies. This will be part of the work of the Church Council towards a final tabernacling proposal.

But there is another “not knowing what we say” which has to do with the very nature of the church as the people of this mysterious transfiguring God.

We have spoken about the fact that change is inevitable. When things are more or less comfortable, more or less easy, change becomes something we endure rather than embrace. To endure what happens next is to doubt that God could look anything different from what God appears to be here and now. To embrace what happens next is to expect God to be transfigured for us but still be the same God. This transfiguration won’t be a mystical mountaintop vision but perhaps a re-discovering of God in a house of sticks or straw after having we have known him in a house of bricks. To embrace what happens next is not to know that it is right, but to commit to it being right and then discovering how – in God – it can be. And if it is truly a choice for this God, what we have chosen will be both wrong and right: we didn’t expect that, but we needed it.

In a couple of month’s time we will hear a proposal from the Church Council which will be put for all sorts of good reasons, and in Peter’s sense we won’t know what we are saying, or choosing. If we are to continue to represent what we think MtE has stood for up to this point, what is required from every one of us is the expectation that God will meet us in some unexpected transfiguration, whether our next thing is a house of bricks or that we become members of someone else’s household.

The deep ironic truth in Peter’s “let’s build a tabernacle” is that a tabernacle is built for Jesus in the gospel. It is just that his tabernacle is made of only two pieces of wood joined in the shape of a cross. And, to recast his call to discipleship, this Jesus says to us: whoever would be my disciple must take up his tabernacle and follow me. This is not a call to mere self-sacrifice on a cross. It is a call to believe in the God who raises the dead.

This we say, not really knowing what it means, but that it matters. For we do know that tabernacling God, the giving of flesh to our faith, becoming the Body of Christ: this is the end of all things, the goal towards which all creation is oriented, and what God most earnestly seeks. To hope that we will faithfully be the church in all that we choose is to hope…we’re not quite sure what, but we know that it matters.

To say it again, what is required of us now is the expectation that, whether it is on a mountaintop or in the last place we might have imagined MtE to end up, Jesus will meet us there and, in his own strange way, will remake us and renew us.

The dwelling we seek to build is not about mere space. It is about place: life in all its fullness. The tabernacle of Jesus doesn’t finally house him but us; he is a place for us in God, wherever we find ourselves in the world. And we will discover ourselves – not knowing how – finally at home.

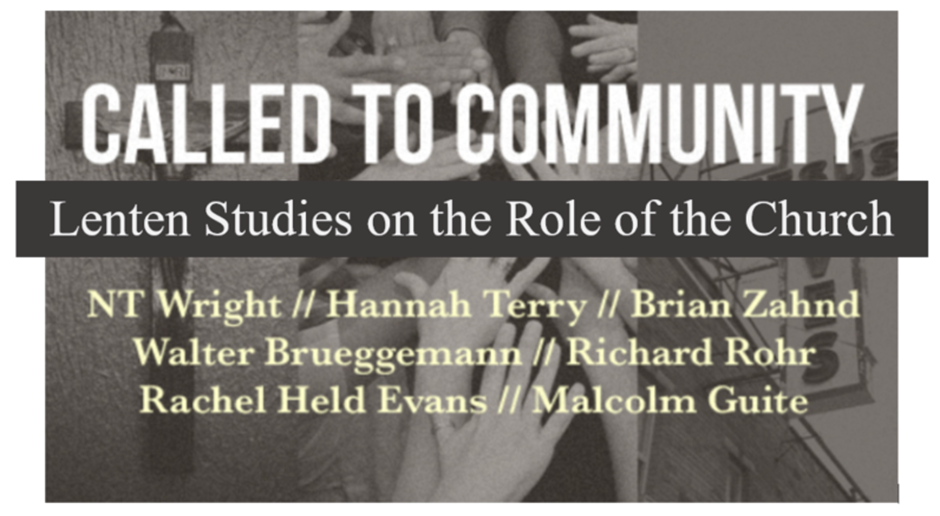

Once again we are joining in a Lenten study series with St Mary’s Anglican Church, North Melbourne, and other ecumenical friends. See

Once again we are joining in a Lenten study series with St Mary’s Anglican Church, North Melbourne, and other ecumenical friends. See