Spring 2023

| From the Minister | Welcome to our Spring 2023 edition of Mark the Word – the first to be published from our new home at the CTM. A lot has happened since our Winter edition, not least that we have packed up and moved from Elm Street and are now becoming accustomed to our new surroundings, although there is still more to be done (see From the Minister). A large amount of work was accomplished behind-the-scenes in order that we could have a smooth transition and we thank the Finance & Property Committee for all of the organising which was needed to achieve this. Some things were fairly simple to move but one item in particular, the relocation of the Midwifery and Mission sculpture, was much more complicated! Alan Wilkinson gives us a very detailed record of this. On 14th October 2023, we will be asked to vote, YES or NO, in the referendum to have the Voice enshrined into our Constitution. We have included two contributions relevant to this issue which will hopefully give us pause to reflect on what decision each of us will make. We also remember our much-loved Church member and friend, Norma Gallacher, with the Eulogy delivered at Norma’s funeral by her sister, Ruth Akie.

From the Editorial team: Rod Mummery, producer, Vicki Radcliffe, Editor, and Rosemary Wearing, Assistant Editor. We continue to be grateful for the generous input to MtW by our congregation. We also thank Rod for his patience and advice and Donald Nicholson for his selection of music. Christian Li and the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra performing Vivaldi: The Four Seasons, Violin Concerto No. 1 in E Major, RV 269 “Spring” – I. Allegro. From the Minister So, now it’s all done! Or at least, the most recent thing we had to do has been done, and now we look to what needs to be done next. Our move into the CTM has been pretty smooth, not least because we haven’t don’t much yet! Now coming up to our sixth week in residence, I suspect that we’ve worked out (more or less) how the kitchen works and where the toilets are. There is much to do, simply to make the place more “ours” and us more part of the place. On the list are improving the sound and lighting, replacing the chairs with something safer and more comfortable, commissioning some appropriate liturgical furniture, sorting out our as-yet-not-sorted storage needs, working out how to hang seasonal colours and probably a new cross in the worship space, installing the new organ, finalising the installation of the Meszaros sculpture, and giving the smaller chapel a run (or two). These are most obvious on a reasonably long list of settling-in tasks. It’s all been rather “seat of the pants” till now, and will likely be so a bit longer, but we’ll keep at it. Our life at the CTM must be our life – something we share and are all part of. So in mid-September we’ll take a moment to share our experiences of moving into the CTM to date, and begin to get a bit more deliberate about moving towards making it our home, and not just the place where we worship. Looking back at one of my old Mark the Word pieces – written just as we began the MtE Futures Project which has led us to the CTM – I saw that I then remarked that the trick in negotiating what was ahead of us would be this: to engage not in dreary property development or divestment but in a joyful work of love in God’s garden (2015 – it had a strong “spring is in the air” theme!) I don’t know that the Futures Project eventually developed into what we would call enjoyable gardening, but I do think there’s rather more promise of that possibility now. Let’s make that happen. News from Church Council The winter Church Council news reported the important decisions of the Council and Congregation that would enable an imminent move to the Centre for Theology and Ministry in Parkville. And so it came to pass! Mark the Evangelist is now resident at the CTM, and the first weekly service was held on 23 July in the Yuma Auditorium (formerly named Wyselaskie Hall). The transition has been smooth, and it’s clear we are quickly becoming accustomed to the new setting, grateful to continue to worship in the ways that we value so much. It’s handy that morning tea is served only a few steps from the auditorium. Meanwhile plans are gradually being made for new seating, improved lighting and so on. The successful move to the CTM has happened, above all, thanks to the huge amount of careful planning and hard work by the Finance and Property Committee – Rod, Alan, Craig, David R and Greg Hill. Before the move to the CTM occurred, the Council was keen to mark fittingly the end of worship at the Curzon Street site. Invitations were extended broadly for a final worship service on 16 July in the Elm Street Church to give thanks for generations of worship that took place in North Melbourne. The service, and the generously catered lunch that followed, were well attended and included former members and others with a close association with Mark the Evangelist. Last month the congregation received the sad news of the death of Norma Gallacher on 19 August. Norma had attended church the previous Sunday, as she had done throughout her long illness. We remember Norma fondly and reflect on her many gifts, none greater than that of warm and faithful friendship for which she was much loved. Many members attended her funeral service on 24 August. We pray for Rob and the Gallacher and Woolhouse families. Comments, queries and suggestions are welcomed by the Church Councillors: Midwifery and Mission: bringing forth life out of darkness Our Congregation took great pride in the unveiling of this sculpture on the forecourt of Union Memorial Church in Curzon Street North Melbourne on the occasion of the 150th Anniversary (2004) of the worship of our church on this site.

After carefully examining a number of options, the Congregation resolved to move its worship services to Yuma Auditorium at the Centre of Theology and Ministry (CTM) in Parkville. Along with these momentous decisions, the Congregation decided it wished to ‘carry’ with it one of its key treasures – the sculpture by Anna Meszaros it had titled “Midwifery and Mission: bringing forth life out of darkness”. Following consultations with the Centre for Theology and Ministry, it was determined that the sculpture should be located at the front of the CTM building. Mark Zhuang was contracted to effect the relocation, the first step being to prepare the new plinth on which the bronze sculpture and its granite backing stone would be mounted. The foundation hole was excavated, and a one cubic metre concrete pour established the base. The base was levelled and reinforcing rods were inserted to stabilise the soon-to-be poured plinth.

This was no easy task! Anna Meszaros, the sculptor, recalled that three or four steel pins had been used to locate and fix the sculpture block on top of the plinth – using ultra-strong construction glue. It was therefore necessary to drill two holes through the top of the plinth, through which the yellow straps could be threaded. This would create the sling to hold the block while the plinth underneath the block was demolished to lay bare the steel locating pins. Only then could the sculpture and its block be separated from the original plinth.

Using the caterpillar lift the sculpture block was first gently lowered to the ground and laid on its back to enable the sling to be re-adjusted for a horizontal lift. It could then be lifted onto the tray of Mark’s flat-top truck for transportation to the CTM. Once at the CTM, Mark’s team set about cleaning the steel pins to be ready for the location and gluing of the sculpture and block on the new plinth.

With this part of the relocation completed, Mark’s remaining task at Curzon Street was to demolish the rest of the original plinth and restore the bricks in the forecourt. Again, because of the unduly high strength of the original concrete, it took Mark’s team another three or four days to achieve this with a combination of the caterpillar jack-hammer and other heavy duty equipment.

The work on the sculpture is not quite yet complete. The plinth is to receive a final cement render to Anna Meszaros’ satisfaction to ensure its surface is even and unblemished. But Anna has already refurbished the bronze sculpture and it now looks brand new.

Voice of Country, Voice of the Divine On Sunday, 3rd September, 2023 at St. Stephen’s Anglican church Richmond, a Victorian Student Christian Movement (SCM) Prayer Service “Acknowledgment of Country” was held. This was organised, prepared, written and presented by Rev. Dr Alexander (Sandy) Yule, Rev. Duncan MacLeod and others. Wendy Langmore and Rosemary Wearing gave the readings, and John and Jeanie Adams offered the prayers. It was a profoundly moving Service which included a reading of “The Uluru Statement from the Heart” and a “Prayer for Reconciliation in Australia” written by Elizabeth Pike. Below is the sermon given by Rev. Dr Garry Deverell. Texts: Isaiah 55:10-13; Mark 9:2-8 Last night I made an airport run to pick up Lil. The plane was running late, as usual, so I parked in the official waiting area which is adjacent to a large field of grasslands. No doubt, before too long, the grasslands will be lost to parking or some other kind of built encroachment. But, for the moment, the grass survives. And so do the wallabies that depend on its being there. Last night a mob of about six or seven of them chose to graze right in front of me, occasionally raising their heads when there was a loud noise or a flash of lights, but otherwise entirely engrossed in getting some nutrition on board. The mob remained there peacefully until a carload of humans decided that snapping some photos was the thing to do, at which point the wallabies bounded away. There’s a little parable in this, for those who have the ears to hear. The divine is like these wallabies grazing on the edge of town. They are unique and beautiful in form and movement. They move together as one, each individual tuned in to the extended senses of the mob as a whole organism. They are one in purpose. They take what they need from country, but no more. They live together in peace, looking out for each other. They have no interest in fighting other species. When danger arrives, they move on. They look for another place of safety. Most interesting of all, to my mind, is the fact that wallabies have no loud voice or call of their own. Their vocal cords are barely there, so they communicate by making soft clicking noises, or by gesture or posture, or by pounding the ground with their feet. So wallabies are truly creatures of the margins. They live on the edge of town. They communicate with still, small, voices. They move on when they sense danger. There is surely something of the divine in this marginality. For have we not exiled the divine voice to the margins of our human concerns, to the darkness at the edge of our towns? To my mind, the piece that is missing in the shouty debate about the Voice to Parliament is the relatively still, quiet, voice of country: of the lands and waterways which, in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander dreaming stories, are fecund with the wisdom of the ancestral beings who gave life to us all. We hear these ancestral voices in birdsong and the breezes though the trees, in the rush and trickle of water, and in the clicking of wallabies as they talk to each other. Their voices speak to us of Anaditj,* the ‘way things are’, and our right and proper place in this way. They show us, if we will trouble to learn their language, how to live sustainably in country as kin or family, rather than annexing, using and exploiting country as though it were our slave. The voices of the ancestors show us how to take from country what we need, but no more. They reveal to us the dangers of making ourselves kings over country rather than citizens of her commonwealth. It is intriguing to me, as a trawloolway man, that the wisdom of the Christian Scriptures so often aligns with the wisdom of country. Consider, for example, the last part of Isaiah 55, where the word of God is compared to the rain and snow that water the earth and make it fruitful. The joyful return of the exiled Judahites to their own land is compared to the restoration of a ravaged and neglected countryside to its former glory. The trees are said to ‘clap their hands’ and the mountains and the hills to ‘burst into song’ when country is restored. There is divinity in country, you see. When country is alive and well, when we as human beings are singing with its songlines rather than against them, the presence of the divine is easily discerned and celebrated. But when we ignore the voice of country, when we can barely remember its ways, country languishes and then we languish. And the still, small, voice of the divine is exiled to edge of town. When the divine voice calls out, atop a mountain in St. Mark’s Judea, saying that Jesus is the beloved of God and that we ought to listen to him, Aboriginal readers hear a call to listen to country. The usual historical-critical reading of the story is that Jesus, having preached and healed his way around Galilee, here consults the law and the prophets to figure out what he ought to do next. The law and the prophets, here represented by Moses and Elijah, tell him to turn his face toward Jerusalem, and to do so in the confidence that his death at the hands of evil men will nevertheless reveal a persisting divinity, a fundamental perseverance for life, that even death cannot overcome. Thus, the transfiguration is understood to be St Mark’s version of the resurrection. A momentary shining forth of the promise of things to come. Which is all well and good, if you think this story is primarily about human beings. But this trawloolway reader thinks there is something else going on here. For the story takes place in the mountains, which are usually alive with ancestral presence. And there Jesus meets with the ‘old people’, ancestor-creators, who share with him their knowledge of the ways things are, of the dreaming, of things that were, and are, and are yet to be. And Peter recognises that they are divine beings, and that Jesus is a divine being, for he proposes to make a tabernacle for each of them, that symbol of divine dwelling from the history of the Exodus. And the voice that addresses the disciples, at the apotheosis of this strange encounter, comes not from a person at all, but from a cloud. It is the voice of country, of the other-than-human world, who identifies Jesus as it’s voice, it’s kin, it’s wisdom made flesh. So, as the referendum on a voice for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people approaches, let us indeed listen to Jesus. For, in his parables, he speaks for and from country, he speaks of country as the place where the will and way of the divine can be discerned. Whether his metaphors are taken from the birds of the air, or the fig tree, or the making of pearls, Jesus assumes that country is our teacher. And when he speaks of himself as the seed that must die to live and be all the more fruitful, he identifies himself with country (Jn 12:24). That is why, in the theo-poetics of native peoples, Christ and country stand in for one another, represent one another, speak for one another. That is why I say to you now: to listen to Jesus is to listen to country. To listen to country is to listen to the oldest and the wisest of our First Nations elders. To listen to the oldest and wisest of our Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander elders is to give country a voice. And that, I would submit, is the most important thing to realise about the coming referendum. For, in the colony of Australia, we lead the world in destroying our environment and endangering the future of our furred and scaled and feathered kin. It is time we stopped. It is time we listened. It is time we wised up. * ‘Anaditj’ is a concept in Adnyamathanha language, brought to my attention by Auntie Denise Champion in her book of the same name. Published with the permission of Rev Dr. Deverell. Yes and No Next month we will have an opportunity to alter the Constitution to recognise the First Peoples of Australia by establishing an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice. As I walk through the streets of Port Melbourne and along the foreshore, I try to imagine the lost world of Derrimut, a twenty-something who was the younger of two Arweets (leaders) of the Yalukit-William clan, the river people of the Boonwurrung language group whose country was the coastal strip across the top of the bay, Nerm. Our house is built on reclaimed land, the site of a former lagoon in the Birrarung delta that provided seasonal resources for the Yalukit-William. The arrival of the settlers in 1835 turned Derrimut’s world upside down, and the way of life of the Yalukit-William was swept away in less than a generation. The profound sense of despair, resignation, and fatalism in response to the loss of his land and way of life is captured in the following exchange between Derrimut and William Hull presented as evidence before the Select Committee of the Legislative Council on the Aborigines in 1858. ‘Me plenty sulky you long time ago, you plenty sulky me; no sulky now, Derimut soon die,’ and then he pointed with a plaintive manner, which they can affect, to the Bank of Victoria, he said, ‘You see, Mr. Hull, Bank of Victoria, all this mine, all along here Derimut’s once; no matter now, me soon tumble down.’ I said, ‘Have you no children?’ and he flew into a passion immediately, ‘Why me have lubra? Why me have picanninny? You have all this place, no good have children, no good have lubra, me tumble down and die very soon now. I am a beneficiary of the world that engulfed Derrimut. He was a contemporary of my great-great-grandparents, Amos and Sarah Radcliffe, who married in Melbourne in 1854. They sought their fortune in the Victorian goldfields and began to raise a family there. In contrast to Derrimut, and many of his kin, they had hope for the future as they sailed to Brisbane in 1861 to try their hand at farming.

Coming to church in North Melbourne each week from Port Melbourne, we were travelling from Derrimut’s country to the place where he spent his final days. The small bluestone church, now on Elm Street, was erected on Curzon Street in 1859 in the shadow of the Benevolent Asylum. In the early 1860s, Derrimut was admitted to Melbourne Hospital on several occasions before being transferred to the Asylum. He passed away there, aged just 54, in April 1864. I wonder if he was able to catch a final glimpse of the Birrarung delta and Nerm, his land and sea, from the Asylum given its elevated position? Even though the Congregation of Mark the Evangelist has now moved to Parkville, the story of Derrimut follows us. Just across College Crescent from our new worship home at the CTM is the grave of Derrimut, not far from the Prime Minister’s Memorial Garden.

The inscription reads, This stone was erected by a few colonists. To commemorate the noble act of the native Chief Derrimut who by timely information given October 1835 to the first colonists. Messrs Fawkner, Lancey, Evans, Henry Batman and their dependents saved them from a massacre, planned by some of the up-country tribes of Aborigines. Historian Ian Clarke argues that the importance of Derrimut in the early history of the settlement of Melbourne cannot be overstated. Principally remembered for his role in preventing the massacre, Derrimut remains a controversial figure. His contemporaries and later scholars have characterised him in a variety of ways, summarised here by Clarke. William Buckley wanted to spear him for his actions; Massola considered he was a traitor; Christie a collaborator; Christiansen ‘a go-between’; Griffiths a person who ‘crossed the boundary’ and ‘betrayed his people’; and Barwick ‘the saviour of Melbourne’. However, these judgements need to be balanced against his actions in the late 1850s and early I860s when he unsuccessfully fought to protect Boon-wurrung rights to live on their traditional country at Mordialloc. When this reserve was finally taken from his people in July 1863, Barwick asserts Derimut became half-crazed with remorse and drank himself to death within the year. Derrimut was a young man caught between worlds, a ‘culture-broker’, living at the intersection of the newly imposed ‘law’ and his timeless ‘lore’. His is a complex story that cannot be adequately expressed in a few sentences. My purpose for reflecting briefly on his life and fate is to illustrate how close we are to the issues canvassed in the Uluru Statement from the Heart and hence the upcoming referendum if we choose to look. YES, the decision to change the Constitution requires thoughtful reflection about the past, present, and future of this ancient land. The issues are not distant or remote or somehow decoupled from our comfortable lives. There are NO simple answers. Reconciliation will be a long and sometimes painful journey together. Vale Norma Gallacher

Her father was the Methodist minister of the Longford circuit. He was then appointed to Wycheproof, Victoria where Norma commenced school. Her education continued at Mooroopna and Eastern Road South Melbourne, followed by Middle Park Central, then Mac Robertson Girls High school. She trained as an Infant teacher at Toorak Teachers College and commenced her career at South West Brunswick. By this time her dad was the minister of the West Brunswick circuit and Norma was assisting as a Sunday School teacher and youth leader. Norma compiled several books about her life, and family, and her ancestor, Mary Curnow. She had a passion for reading and at different times belonged to Book Clubs right up until her death. Before her marriage Norma competed in Athletics for Victorian Railways Institute. She was an excellent sprinter and hurdler. She played tennis, badminton, and coached basketball teams. She was a member of the Victorian Methodist State Basketball team (now called netball). Norma was a leader for several years at Methodist Girls camps at Clevedon (in the Dandenongs) and at Ocean Grove. Norma used her musical talent to assist at church and Sunday school. She learnt to play the pipe organ.

So began a lifelong partnership supporting each other in their interests and work. One illustration is the tribute by Rob in his book ‘Colour of Prayer’: “In closing I want to acknowledge the loyal and constant support of my wife Norma. She has trudged around churches in many countries, helped with exhibitions, attended classes and been my aid at presentations. She has never failed to be encouraging, even when criticizing.” Rob’s first ordained appointment as a minister was Dunolly where Frank and Lynette were born. His next appointment was Boort before their time in Cambridge England where Rob was studying. Norma had several teaching jobs there as well as in London while Rob was studying in Switzerland. She and the children joined him before they returned to Australia. They later had many overseas holidays – all taken with a purpose for further education. In 1970 they returned to Melbourne for Rob to take up an appointment at Malvern. Norma taught migrant English prior to Todd’s birth. Norma has had great joy being a mother: and later grandmother – to Ella and Zoe. She was proud of all the family. This included later Michael and Cath, partners to Lyn and Todd. Next, they served at Glen Waverley and Norma contributed to the congregation in her own quiet intuitive way, especially teaching Sunday School. Glen Waverley at that time was a vibrant place, full of young families and activities Norma completed her Special Education training and taught at Glen Waverley Special School After Norma and Rob moved to Geelong and then Drysdale, she continued as a Special Education teacher in Corio. Norma’s family ties were strong and she treasured time spent with her children and siblings The Woolhouse girls were a force to be reckoned with! The last six difficult years were made so much more bearable with the arrival of Ella and Zoe whom she loved very much. After retirement from teaching Norma did many voluntary jobs – these included the Alfred Hospital as a chaplain, the Commonwealth Games, the South Sudan migrant Kindergarten in Melbourne, Trading Partners and the Melbourne Writers Festival. Most specially in recent years was her involvement with the Choir of Hard Knocks. Norma has always been a people person within church activities, community and particularly her immediate and extended family. Her cancer diagnosis six years ago was a shock to us all, but in the end it was not the cause of her unexpected death. Norma kept the faith to the end, praise God. Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck: Onder een Linde Groene played by Marco Vitale |

Despite the Congregation’s best efforts over more than ten years to either restore our damaged heritage building or develop a new church building on the site, we, Presbytery and Synod together decided that any project would be too costly and too risky. The whole church site bounded by Elm, Curzon and Queensberry Streets was sold, with the settlement on 8 August 2023.

Despite the Congregation’s best efforts over more than ten years to either restore our damaged heritage building or develop a new church building on the site, we, Presbytery and Synod together decided that any project would be too costly and too risky. The whole church site bounded by Elm, Curzon and Queensberry Streets was sold, with the settlement on 8 August 2023. A few days later the formwork for the plinth was constructed and the second concrete pour took place. That concrete block required another three days to set in readiness for the mounting of the sculpture.

A few days later the formwork for the plinth was constructed and the second concrete pour took place. That concrete block required another three days to set in readiness for the mounting of the sculpture. Mark could now turn his attention to the process of separating the sculpture and its mounting block from the plinth in front of Union Memorial Church in Curzon Street.

Mark could now turn his attention to the process of separating the sculpture and its mounting block from the plinth in front of Union Memorial Church in Curzon Street. This proved to be a gruelling task for two manual jack hammers. Mark explained that concrete can be supplied in different strengths for construction work. The greater the load to be supported, the stronger the cement mix needed to be. In his assessment, the original concrete plinth had been constructed with a super-strong cement mix which was proving to be particularly difficult to break down. All that said, Mark and his team eventually managed to smash the plinth away from around the four steel connecting pins and the rock-solid construction glue. At last, the two-and-a-half-ton sculpture block was free and was ready to be transported to the CTM in College Crescent.

This proved to be a gruelling task for two manual jack hammers. Mark explained that concrete can be supplied in different strengths for construction work. The greater the load to be supported, the stronger the cement mix needed to be. In his assessment, the original concrete plinth had been constructed with a super-strong cement mix which was proving to be particularly difficult to break down. All that said, Mark and his team eventually managed to smash the plinth away from around the four steel connecting pins and the rock-solid construction glue. At last, the two-and-a-half-ton sculpture block was free and was ready to be transported to the CTM in College Crescent. Finally, the sculpture is mounted in its new location at the CTM.

Finally, the sculpture is mounted in its new location at the CTM. Who would know that a sculpture had been removed? Just in time for settlement of the sale on 8 August.

Who would know that a sculpture had been removed? Just in time for settlement of the sale on 8 August. It remains for us to modify slightly and reproduce the plaque with the “Midwives and Mission” narrative, among other things to acknowledge its original commission at Union Memorial Church and its relocation to the Centre for Theology and Ministry.

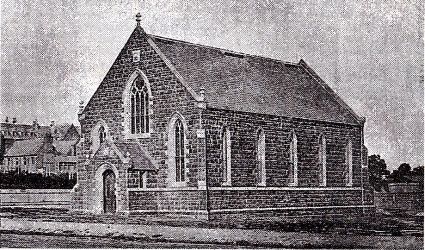

It remains for us to modify slightly and reproduce the plaque with the “Midwives and Mission” narrative, among other things to acknowledge its original commission at Union Memorial Church and its relocation to the Centre for Theology and Ministry. Benevolent Asylum (left) and Bluestone Church (centre), North Melbourne

Benevolent Asylum (left) and Bluestone Church (centre), North Melbourne Derrimut’s Grave, Melbourne General Cemetery

Derrimut’s Grave, Melbourne General Cemetery Norma was born in Launceston, Tasmania on 13th May 1938. She was the fourth child out of six, of Frank and Amy Woolhouse (Nee Curnow).

Norma was born in Launceston, Tasmania on 13th May 1938. She was the fourth child out of six, of Frank and Amy Woolhouse (Nee Curnow). Norma and Rob were married on 23rd of December 1961 at Daly Street Methodist church West Brunswick. The service was conducted by their fathers, both Methodist Ministers.

Norma and Rob were married on 23rd of December 1961 at Daly Street Methodist church West Brunswick. The service was conducted by their fathers, both Methodist Ministers.