Spring 2017

| Introduction

Book review: The embarrassed colonialist Euthanasia in biblical and theological perspective |

Introduction Again we have an interesting variety of articles contributed by the members of the congregation. As Suzanne is not available to produce this edition the task has fallen to me. I’m most grateful for all the contributions which all arrived with very little promoting on my part. We start a reflection from Craig. Rosalie gives us an update on Akbar’s situation. We then have a book review written by Suzanne for Crosslight. This is followed by a thought provoking abbreviated/edited version of a document on Euthanasia prepared by the UCA’s bioethics committee (Rosalie was a member and secretary). We learn things about Donald from an interview courtesy Classic Melbourne. We then venture to Ethopia with Rob’s musings on their trip before returning home with a report from the Church Council. Finally we finish in a light hearted manner with Rosemary’s alternative to the formal Annual Report! Rod Mummery To continue our tradition of having some music to listen to, and being the Spring edition what else is there but Vivaldi’s Spring from his Four Seasons. A YouTube search unearthed a local ensemble whose web site describes them thus: “The Melbourne String Ensemble is a dynamic and exciting Orchestra of secondary and tertiary students performing high quality String repertoire which places importance on developing the ensemble and musical leadership skills of its members.” From the Minister Over the last month or so I’ve been greatly enjoying a book – The Great Code: the Bible and Literature – which has sat on my shelves for I don’t know how many years until its Contents page popped in a search of electronic notes on my computer (how did people find anything in the days of file-card systems?). God moves in mysterious ways. A quick peak revealed that here was something which might help with a couple of conversations to which I’ve been party. A full read revealed a treasure trove of insights and revelations such as I’ve rarely encountered. Northrop Frye’s purpose in this book is, on one level, to unpack the literary character of the Bible – the kind of literature it is, what makes it “tick”, how it “works”. Alongside this, he shows how the Bible-kind of discourse differs from ours in ways which most of us would miss unless a Frye or someone else pointed it out for us. Having demonstrated these characteristics, Frye then offers something of a tour de force of the Scriptural narrative, but a tour now with headlights fitted more powerful than what I, at least, have been using to see a way into the text. All sorts of unexpected things are appearing in shadows I had not even noticed were there. I’ve discovered in Frye an invitation into a more “organic” reading of the Scripture which, for me at least, has been very refreshing. The fruit of this reading is appearing now in my preaching; I hope it’s being found by others to be sweet! The Great Code is not a book for the faint-hearted; it would probably help if you’ve read at least some of the Western literary canon (I’ve read scarcely any of it!) but a knowledge of the Bible and a thirst for deeper understanding of it would be firm enough ground on which to build a way into Frye’s stimulating account. Yet my point is not quite to encourage you to run out and buy a copy for yourself. I want, first, simply to share my joy – not a word I “own” very often! – at being caught by surprise by Frye. It’s a joy to discover something like this after 25 years of digging pretty deeply into things theological and beginning to imagine that I might know what might be found where (so, why keep digging?). It rekindles the hope that there’s yet more brilliant light still to shine forth from other sources as well. But, second, it strikes me also that Frye is now more than 25 years dead, long past knowing or caring what has come of his work, and yet it continues to create ripples and make an impact in ways he would not even have known if he were alive. I take encouragement from this lingering effect of a life and ministry, and invite you to, as well. Our work for the good is – in this God’s hands, and whatever we think we are doing at the time – work for goods we will not fully see or know. As a congregation we cannot know what difference we will have made 50 or 100 years from now, and yet we trust that we are to continue in faithful response to our sense of call to worship, love and serve, and so we do. It is not different with our individual responses. But this makes me think another thing. Perhaps there is not much difference between how a good we do works here and now and how it might work after we’ve gone. That is, we do not really know the good we do, even as we do it – the effect of a kind word, or a donation, or a phone call. These things take on a life of their own when they leave us, becoming often much more than we could imagine. Not to do the good because can’t see what good it would do, would be to insist that it’s only what we can see which matters. But God’s sees further than we, and it’s on God’s sight lines that our good is carried forward. Let us, then, do whatever good we can, and then watch to see – as long as we can see! – what unexpected things God will make of it. Akbar: our neighbour in need

Transferred to MIDC (Maribyrnong Immigration Detention Centre) he found himself imprisoned once again; not once leaving the centre in two years. He despaired of seeing anything of Australia beyond the barbed wire. When transferred to MITA (Melbourne Immigration Transit Accommodation) in Broadmeadows he found the conditions slightly more tolerable. However, he reported being given six tablets each night. ‘At first, I refused, then I couldn’t be bothered saying no’. In his 44 months in detention he was assigned eleven different case managers. ‘I only trusted one, then he left.’ His increasing despair resulted in him cutting his throat in early 2013; with no follow-up treatment after hospital discharge. Judy Dixon, a dedicated, experienced and highly qualified pro bono migration agent, joined me in making several appeals to the minister for immigration for Akbar’s release, together with a thorough assessment and letter of appeal by a prominent professor of psychiatry. On election eve, September 2013, Akbar was finally released from detention with a temporary (six month) bridging visa signed by the minister for immigration. As for many refugees, freedom does not necessarily mean immediate relief, particularly when given thirty minutes notice and $50 to find their way to the external world. After a period of insecurity Akbar finally settled at ‘Sanctuary’ in Preston, a boarding house run by ‘Baptcare’ for 40 single male asylum seekers of various nationalities. Meals are not provided; however, there is a communal kitchen where (when in a positive mood) he is able to cook for himself. He has few friends and remains for the most part, isolated in his room. ‘I sleep all day’, he says, readily admitting to being ‘addicted to sleeping pills’. All attempts to obtain a permanent visa have failed. He says, with despair: ‘I cannot stay in Australia and I cannot return to Iran’. ‘But’ he says, ‘I want to contribute to Australian society by working and paying tax’. His perception of ‘hopelessness’ is exacerbated by his longstanding depression; perpetuating a cycle which he seems unable to break. After four years in ‘Sanctuary’ he says, ‘I still feel like I’m in prison, as I’m not free. I have no future.’ I have been visiting Akbar fortnightly for five years, as well as writing numerous letters of appeal, the latter also supported by John Langmore. I attended a meeting recently at the Immigration Centre, about supporting asylum seekers, and I was very pleased to hear about which shows that, while individuals cannot do much about the 30,000 refugees in Australia, we can ‘move mountains’ by maintaining regular contact with one. Akbar is also supported in many practical ways by John Hood, and a recently acquired friend – an Iranian university professor (who has been in Australia for 30 years) – who visits regularly. Akbar’s weekly highlight is his few hours’ gardening work in North Melbourne. He also enjoys watching movies on the laptop computer so generously donated by members of Mark the Evangelist. Special thanks to those members of our congregation who have continued (for four years) to make regular cash donations. Your heartfelt, practical generosity is never taken for granted by Akbar. ‘Tell your church people Akbar says thank you.’ For others who wish to join this support network, cash donations may be given to me or to Rod Mummery in my absence, on any Sunday. Strongly recommended reading: They cannot take the sky: Stories from detention (2017) edited by Michael Green and Andre Dao. The embarrassed colonialist Historic truth Book | The embarrassed colonialist | Sean Dorney

But, Dorney asserts, this isn’t happening. Instead, Australia is “the embarrassed colonist” of the title. This reluctance to be involved with PNG, or even to take a detached look at our past relationship with that country, does neither country any good and needs to be reassessed as well as understood, the writer argues. That Australia has always found PNG ‘difficult’ to understand and manage is hardly surprising. Read the rest of the review in Crosslight Euthanasia in biblical and theological perspective This is an abbreviated/edited version of a document prepared by the UCA’s bioethics committee in 2011. The 110-page text ‘Abortion and Euthanasia’, was to be submitted for publication when the Synod disbanded the committee (Chair: Rev Ross Carter and Secretary Dr Rosalie Hudson). Made in the Image of God. From the doctrine of creation, we learn that God is both the origin and destiny of created human life: our beginning and our end. Made in the image of God, our worth and dignity as unique persons is a gift of grace. Hence all human life is precious in God’s sight; whether unborn child or older adult, whether healthy or malformed, underscored by the gracious commandment, ‘Thou shalt not kill’ (Deut 5:17). From the doctrine of the trinity we learn that we are made for fellowship with God and with each other; we live only in relationship. From St Paul, we learn that in ‘the body of Christ’ (1 Cor.12) all members are equally important to the whole and that the weakest members are to be respected and loved. Questions of biological life and death have been decided through the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ. The strong consensus throughout church history is that Christians never aim at death, as an end or a means to an end, either for themselves or others. Autonomy and dignity. Many proponents of euthanasia are concerned about autonomy and dignity, believing we should have choice and control over the time and manner of our dying. Some would argue that legalizing euthanasia may lead to vulnerable, disabled and/or elderly people being placed under pressure to seek death rather than be a burden on their loved ones. A mother of a large family repeatedly asserted: ‘I wish I could go to sleep and not wake up’. She had no pain and said she was comfortable. Hospital staff believed she was requesting euthanasia. Finally, it was discovered that she was concerned that her family had gathered, some from interstate, to be with her, believing she was close to death. Unexpectedly, her condition had stabilised; but she felt she was interrupting the family’s busy lives and did not want to impose further burden on them. After open discussion, arrangements were made for interstate family members to return home and for her to be transferred to the local nursing home where she continued to live for some months. This story shows how important it is to uncover what is underlying any request (or perceived request) for euthanasia and to acknowledge that none of us is totally autonomous; we need each other. Our ‘dignity’ is also, in the words of the hymn writer ‘Be Thou my dignity’ located outside of ourselves. Palliative care. Palliative care recognises that even when we cannot cure we can care. To ‘palliate’, derived from the Latin, means ‘to cover with a cloak’. This cloak of care is not confined to the last stage of illness. Some people recoil from the term ‘palliative’ in the mistaken belief that it suggests ‘giving up’ or ‘no more treatment’. The benefits of palliative care earlier in the illness include improved pain control, effective symptom control, reduced anxiety, fewer hospital admissions, less care-giver distress and reduced costs. The result is better living, not just easier dying. Palliative care is for those needing assistance due to any chronic, incurable illness. Suffering. The capacity to suffer, to bear grief and misfortune, is, along with our capacity for pleasure, joy and happiness, what makes us human. Humanity cries out for the removal of suffering, especially in view of our helplessness in ‘hopeless’ situations. However, we may not stand idly by and watch a person suffer. We must seek the best available means of response – medical, therapeutic and pastoral – to relieve unnecessary pain; together with patience and courage in the face of the suffering we cannot totally alleviate. Biblical faith demonstrates that suffering never removes us from the loving care and mercy of God. Thus, quality of life and sanctity of life are not opposed; in Christian terms, they are complementary. Care for others. The challenge for Christians is how to care for people who find themselves increasingly dependent on others; particularly those approaching death. We demonstrate the compassion of Christ by faithful service to those in need. In the face of death Christian hope is in Jesus Christ who said: ‘I am the resurrection and the life; those who believe in me, though they die, yet shall they live; and whoever lives and believes in me shall never die’ (John 11: 25, 26). Donald Nicolson plays Bach

Born in Wellington, New Zealand, and now a Melbourne-based harpsichordist, organist and pianist, Donald Nicolson is a prominent figure in performance and research of the music of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Europe, continuing to work on both sides of the Tasman as keyboardist for the ACO, MSO, SSO, and New Zealand Symphony Orchestra. He has directed numerous performances from the harpsichord including the Melbourne Symphony and Australian Chamber Orchestras, and teaches baroque practice at the University of Melbourne. The congregation of the North Melbourne Uniting Church know him as a fine organist with a penchant for adding ornaments to the simplest of Wesleyan tunes! What gave Donald the idea of being a professional harpsichordist? Read the full interview at Classic Melbourne There and Here – Musings After a Brief Visit to Ethiopia After two weeks in the country, I cannot presume to speak with authority about Ethiopia, but I can tell you my thoughts about some of the bits I saw.

Perhaps it was my defence mechanism that caused me to focus on some down sides to this well-established Church. (Ethiopia became Christian about 350 AD.) I visited several projects teaching skills to women, to elevate their status in village life. But it was said that the Church was not supporting the advancement of women in either society or Church. The conservatism of the Church was shown in another way. It is claimed that the Queen of Sheba had a son whose father was Solomon. The emperors since then have been of the line of Solomon, and they have the Ark of the Covenant from the temple in Jerusalem to support it. A replica of the Ark is located at the centre of every church, and is taken out to lead huge processions at major festivals. However the line of Solomon was lost when Heile Salasse was exiled and the foundational myth which the Church still maintains is now out of date. On the other hand, this Church, seemingly moribund, has maintained its vigour through two secular, atheistic, Marxist regimes. How do we get on with foundational myths? Our Church claims to be apostolic, but many inconvenient Biblical passages are sacrificed in the name of relevance. Multi-culturalism and scientific method have chipped away at Christianity as a basis for public life. Our politicians don’t seem to own much in the way of foundational myth. When the Prime Minister tries to unify his party by an appeal to the Liberalism of Menzies, the party’s founder, it doesn’t work. Why is it that the Churches that sustain the worst kind of conservatism seem to be the ones that flourish? Why does the press only quote the Australian Christian Lobby on the rare occasions a Christian viewpoint is sought? Why does the Church always seem to be on the back foot, unable to present a positive message about the sacredness of marriage, or the view that life is holy and should not be destroyed deliberately, either in war or by euthanasia?

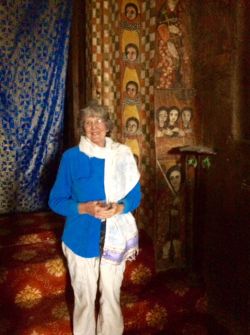

“As the tender flowers, open out their petals, to the sun their hearts unfolding, so may I, calm in joy, hold your rays from heaven, power within me working.” As we sang, my eye went to the brilliant yellow lilies on display that day, and the verbal analogy was enhanced by the visual presentation. So in the Church of Debre Berhan Selassie 144 angels on the roof give immediacy to the words: “And so we praise you with the faithful of every time and place, joining with choirs of angels …. in the eternal hymn, Holy, Holy, Holy Lord…” The faithful of every time and place are generously depicted in the black saints that grace the walls of almost every Ethiopian Church. In the modern cathedral at Axum (where the Ark is kept) the cultural appearance of the icons is maintained in a manner that is distinctly contemporary. In relation to this I put the resolution of our last Congregational Meeting, that the icon writers of the congregation help members appreciate the meaning of icons. Most Sundays we name particular saints from the list in Uniting in Worship, and put words about them in the Order of Service. An icon of the saint for the day could deepen the appreciation of the spirit in that person and lead to a prayerful communion in which something of the saint becomes embodied in the worshipper. Similarly we observe major festivals like Christmas, Easter and Pentecost. Festival icons are so carefully constructed that they can bring the celebration to life visually. A visit to the museum in Addis Ababa gave me pause. I was looking at Lucy, or at least at what is left of her after 3.2 million years. She is not exactly Homo Sapiens, but the bones are without doubt human. As I age, my sense of time is changing. Young people look at me when I say I can remember World War 2. Australia’s 250 years of European settlement is just a flash. As I fill in the ups and downs of the 2,000 years since Jesus walked the earth, the bridge to the New Testament grows easier to cross. “A thousand ages in thy sight are but an evening gone” is one thing, but 3.2 million years is something else. How much history there is before the two or three thousand years we know about! How refined is the oral tradition that developed in myth and legend to deal with eternal truth! Does “resurrection of the body” apply to Lucy? And if not when does it start? Does the constant focus on creationism versus evolution distract us from more significant theological enquiry?

News from the Church Council

Comments, queries and suggestions are invited by the Church Council: Gaye Champion (Chair, UnitingCare Hotham Mission), Michael Champion (Elder), Belinda Hopper (Elder and Secretary), Gus MacAulay (Elder), Rod Mummery (Elder and Treasurer), Tim O’Connor (Elder and Chair), Maureen Postma (Elder), Craig Thompson (Minister) and Alan Wilkinson (MTEFP Coordinator). An Alternate Annual Report Dear Synod, we trust that our Annual Report Outgoing Secretary, 2017 |

Akbar Faridi, in his early twenties (his birth date is unknown; as a stateless Faili Kurd he has no identity papers) paid $12,5000 to come from Iran to Australia by boat in 2009. Prior to fleeing his home country, he had been imprisoned in solitary confinement for 40 days. On Christmas Island, he endured more inhumane treatment so he scaled the fence ‘to see what was on the other side’. When caught he was harshly punished. In his 37 days on the island he sewed his lips together, made 100 knife cuts to his body, and endured other ‘unspeakable’ trauma, both self-inflicted and from the security guards.

Akbar Faridi, in his early twenties (his birth date is unknown; as a stateless Faili Kurd he has no identity papers) paid $12,5000 to come from Iran to Australia by boat in 2009. Prior to fleeing his home country, he had been imprisoned in solitary confinement for 40 days. On Christmas Island, he endured more inhumane treatment so he scaled the fence ‘to see what was on the other side’. When caught he was harshly punished. In his 37 days on the island he sewed his lips together, made 100 knife cuts to his body, and endured other ‘unspeakable’ trauma, both self-inflicted and from the security guards. Sean Dorney is an Australian journalist who has probably been the most trusted voice on Papua New Guinea affairs since he arrived in Moresby as a rookie ABC reporter in the early 70s. His thesis in this slim volume is simply that Australia needs to be more aware and involved in what is happening in PNG, our former Trust Territory. History, relationships of all kinds and financial ties all make this essential.

Sean Dorney is an Australian journalist who has probably been the most trusted voice on Papua New Guinea affairs since he arrived in Moresby as a rookie ABC reporter in the early 70s. His thesis in this slim volume is simply that Australia needs to be more aware and involved in what is happening in PNG, our former Trust Territory. History, relationships of all kinds and financial ties all make this essential. In a first for Classic Melbourne we introduce the artist before his performance, and will follow up with a review later in the week. Donald Nicolson will present The Well-Tempered Clavier, Book 2, Part 1 on Tuesday 22 August 2017 6.00pm at the Salon, Melbourne Recital Centre.

In a first for Classic Melbourne we introduce the artist before his performance, and will follow up with a review later in the week. Donald Nicolson will present The Well-Tempered Clavier, Book 2, Part 1 on Tuesday 22 August 2017 6.00pm at the Salon, Melbourne Recital Centre. Two things that immediately struck me were the poverty of the people and the strength of the Church. Are they related? Conversely, in Australia I see the affluence of the people and marginalisation of the Church. Fifty two percent of the 100 million Ethiopians are Christian. “Do they all go to church?” I asked. “At least half would be regular attenders”, I was told. Observation supported this. All the 30 or so churches we visited had active congregations. Sometimes I saw lines of people reading Bibles outside Churches, even on week days. Groups of pilgrims were encountered at sacred sites. Perhaps home life is so deprived it is good to get out. But then I looked at slum areas and I saw satellite dishes on humpy roofs. It was 9.00 AM one Sunday morning when I asked our young local guide, “Have you been to Church today?” “Yes” he said. “When did you go?” “At 5.00 AM”. “How long was the service?” “Three hours.” I was impressed, and a little guilty as a “Not for me” thought flashed through my head.

Two things that immediately struck me were the poverty of the people and the strength of the Church. Are they related? Conversely, in Australia I see the affluence of the people and marginalisation of the Church. Fifty two percent of the 100 million Ethiopians are Christian. “Do they all go to church?” I asked. “At least half would be regular attenders”, I was told. Observation supported this. All the 30 or so churches we visited had active congregations. Sometimes I saw lines of people reading Bibles outside Churches, even on week days. Groups of pilgrims were encountered at sacred sites. Perhaps home life is so deprived it is good to get out. But then I looked at slum areas and I saw satellite dishes on humpy roofs. It was 9.00 AM one Sunday morning when I asked our young local guide, “Have you been to Church today?” “Yes” he said. “When did you go?” “At 5.00 AM”. “How long was the service?” “Three hours.” I was impressed, and a little guilty as a “Not for me” thought flashed through my head. My primary purpose in going to Ethiopia was to view the art work. In this I was richly rewarded. I didn’t need to be convinced that sacred art can make a significant contribution to worship. It is a visible presentation of the Gospel. In our own Church, on 13th August, we sang:

My primary purpose in going to Ethiopia was to view the art work. In this I was richly rewarded. I didn’t need to be convinced that sacred art can make a significant contribution to worship. It is a visible presentation of the Gospel. In our own Church, on 13th August, we sang: Finally, there was the Sunday afternoon I took Norma to the Hallelujah Hospital. She had picked up a nasty bug. We were greeted by a young female doctor who spoke perfect English. After an initial consultation she sent Norma for path tests, and the results were back in half an hour. In a second consultation she prescribed medication, and our tour guide then scoured Addis Ababa for a pharmacy that was open on a Sunday afternoon. The medication worked a treat. The whole experience cost about $25 Au, and the tour guide paid for it. This is to pay testimony to some of the many wonderful people we met. In the midst of political unrest, poverty, famine and the unreliability of basic services in the third world, there are many dedicated, able, self-sacrificing people. Just as there are here.

Finally, there was the Sunday afternoon I took Norma to the Hallelujah Hospital. She had picked up a nasty bug. We were greeted by a young female doctor who spoke perfect English. After an initial consultation she sent Norma for path tests, and the results were back in half an hour. In a second consultation she prescribed medication, and our tour guide then scoured Addis Ababa for a pharmacy that was open on a Sunday afternoon. The medication worked a treat. The whole experience cost about $25 Au, and the tour guide paid for it. This is to pay testimony to some of the many wonderful people we met. In the midst of political unrest, poverty, famine and the unreliability of basic services in the third world, there are many dedicated, able, self-sacrificing people. Just as there are here.