May 9 – James Egan Moulton

These weekly “People to Commemorate” posts are a kind of calendar for the commemoration of the saints, reproduced here from a Uniting Church Assembly document which can be found in full here. They are intended for copying and pasting into congregational pew sheets on the Sunday closest to the nominated date.

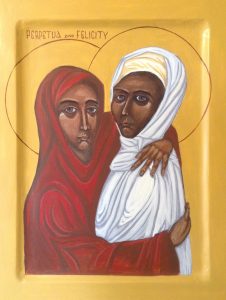

Images (where provided) are of icons by Peter Blackwood; click on the image to download a high resolution copy of the image.

James Egan Moulton, faithful servant

Viewed in the context of Tonga’s Christian history, Moulton is probably the most influential European missionary to have served there. He was born in 1841 into a strong English Methodist family, one of four brothers all of whom were gifted and made great contributions to the fields of literature and education. A scholar in both Hebrew and Greek, James Egan offered for foreign missionary work. Arriving in Australia in 1863, Moulton was detained for two years in Sydney where he married and was appointed the founding headmaster of Newington College when it was situated in the colonial home at Silverwater formerly owned by the explorer Blaxland; for many years the institution served as both Methodist Theological College and boys’ school.

Altogether Moulton spent almost 35 years in Tonga (1865-88 and 1895-1905). He made particularly significant contributions in education, biblical scholarship and translation work. In focussing on these areas, Moulton was not only engaging in his own interests but reflecting the deep educational concerns of Tonga’s high chief and first King, Taufa-ahau or Tupou I. In 1866, Moulton was placed in charge of Tupou College (which opened that year and eventually became the most prestigious school in Tonga). An advanced and progressive curriculum was introduced which cemented educational achievement at the centre of Tongan life. Moulton became an expert in the Tongan language. The historian of Tongan Methodism, Harold Wood, quotes R.G. Moulton (James Egan’s brother) as saying that J.E.M. turned raw Tongan into poetry through his translation of the Bible. He also supplied Tongan Methodism with beautiful vernacular hymns and manufactured a special tonic sol-fa which is still used today by Tongan choirs. In 1899 Moulton was honoured for his academic endeavours with an honorary Doctor of Divinity from Victoria University, Toronto.

Moulton has given Tonga a unique national motto. Observing the generally flat profile of the Tongan islands, Moulton said that “the mountain of Tonga is the mind”. It was largely due to his efforts that the Tongan church placed a great emphasis on the education of their lay people so that today, in Tonga and among the Tongan diaspora of Australia, there is a high value placed on biblical literacy and on the status of lay preacher.

by Dr Andrew Thornley