April 18 – Kentigern

These weekly “People to Commemorate” posts are a kind of calendar for the commemoration of the saints, reproduced here from a Uniting Church Assembly document which can be found in full here. They are intended for copying and pasting into congregational pew sheets on the Sunday closest to the nominated date.

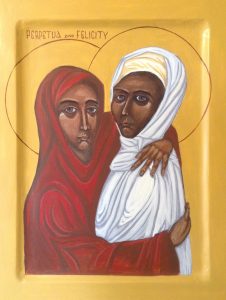

Images (where provided) are of icons by Peter Blackwood; click on the image to download a high resolution copy of the image.

Kentigern, Christian pioneer

St. Kentigern was born about 518 in Culross, Fife, Scotland, to Thenaw, the daughter of a British prince, Lothus. Kentigern, (the name means “head chief”) was popularly known as St. Mungo, meaning “dear one”. He is believed to have been brought up by St. Servanus at a monastery in Fife. His father’s name is unknown.

At the age of 25, Kentigern began his missionary labours at Cathures, on the Clyde, the site of modern Glasgow. He was welcomed there by Roderick Hael, the Christian King, and laboured in the district for some thirteen years. He lived an austere life in a small cell where the Clyde and Molendinar rivers met. By his teaching and example many people converted to the Christian faith. The large community that grew up around him became known as clasgu, meaning “dear family”. The town and city ultimately grew to be known as modern Glasgow.

About 553 a strong anti-Christian movement in Strathclyde compelled Kentigern to leave the district. He retired to Wales, and stayed with St. David at Menevia, later founding a large monastery in Llanelwy and serving as its first abbot. In 573, accompanied by many of his Welsh disciples, he returned to Scotland at the request of the king, after a battle secured the Christian cause. For eight years he continued his evangelical outreach to the districts of Galloway and Cumberland.

Finally, in 581 Kentigern returned to Glasgow, where he remained until his death in 603, continuing his work amongst the people.

Several miracles were attributed to him including restoring life to a bird that had been inadvertently killed, the discovery inside a fish he caught of the missing ring of the Queen of Cadzow, and the rekindling of a fire that he had been tending, but which had gone out. These events are commemorated in the Coat of Arms of the City of Glasgow. The fourth symbol is a bell, believed to have been given to Kentigern by the Pope, Gregory I.

St. Kentigern is buried in Glasgow on the spot where a beautiful cathedral dedicated to his honour now stands. He is remembered on 13 January each year, the anniversary of his death. His humble life, lived in the service of God, affected the lives of many people, particularly in Wales, Galloway and Cumberland in Scotland, in parts of the northwest of England, and, of course, in Glasgow. St. Kentigern is still remembered as a model of how we can make a difference in the lives of others.

Contributed by Sandra Batey